Inhale deeply, fold clothes neatly, five fruits daily, exercise regularly, hydrate constantly, and drive responsibly.

Following wellness advice can be exhausting. As it turns out, belonging to a religion also offers significant health benefits. Studies now show that religious practice leads to an increase in eudemonic happiness. Out of ninety-three observational studies, two-thirds found that religious individuals had lower rates of depression and depressive symptoms. 1

Unfortunately, our current crop of atheist academics lacks the honesty to acknowledge the adverse effects of a godless society. Richard Dawkin, for example, routinely knots himself into an intellectual pretzel trying to articulate morality in an amoral universe. Thankfully for us, Nietzsche thoroughly grasped the social and psychological implications manifested by what he regarded as the extinction of belief. “There now seems to be no meaning at all in existence, everything seems to be in vain”, Nietzsche lamented. His proclamation, 'God is dead,' was not a cry of triumph but of despair. An honest thinker can thus recognise religious systems' immense social, psychological, and personal benefits.

Yet, in some ways, even this positive conception of religion challenges Judaism. Jewish traditions and values may form an impressive edifice, but embracing Judaism's detailed halachic guidelines and legal culture is more challenging. Ideas like Shabbos, for example, are appealing. We can all understand the value of a day for reflection and renewal. Yet it is possible to feel constrained rather than empowered by Shabbos's multi-faceted halachic requirements. Despite our love for Jewish life and moral vision, intense halachic observance and rigorous Talmudic study seem superfluous. How can we address this bone of discontent? And do we need to refine our understanding of what Judaism purports to be?

This week's parsha introduces us to the Mishkann Tabernacle, detailing its intricate building specifications. Outside of exile, the Mishkan's permanent successor, in Jerusalem, becomes a focal point around which Jewish religious life revolves. Indeed the Ramban famously explains that God intended the Mishkan to be a long-term manifestation of the revelation at Sinai, preserving that moment in which we became God's chosen nation by embracing Torah law. The Mishkan's innermost sanctum housed two pairs of luchos brought down by Moshe at Sinai. Significantly, the luchos were placed within the Aaron Hakodesh, a golden ark.

Commentators often see the ark as symbolic of the Torah itself, Judaism's single most essential ingredient and an eternal foundation upon which we build all else. We shall discover that the structural requirements of the ark provide a metaphor with which to clarify what Judaism as a whole is attempting to realise. This will contribute towards answering the question at hand.

God instructs Moshe:

They shall construct an ark out of acacia wood. It shall be two and a half cubits its length, a cubit and a half its width, and a cubit and a half its height. You shall coat it, both internally and externally, with pure gold...

{Shemos 25:10-11}

We will concentrate on two aspects of the ark, its exterior's golden adornment and its interior's wooden structure.

When encountering the ark superficially, one instantly perceives its golden glistening exterior. We can see this as a metaphor for the Torah's overarching expression in this world. How so? As discussed earlier, the encompassing advantages of Jewish life are exceedingly attractive. Even someone without intimate knowledge of its multifarious facets can appreciate the holistic beauty of a Torah-led life. For instance, the bal teshuvah movement is predicated on the understanding that even a passing encounter with Jewish thought will leave a lasting impression on an individual. Educators hope that this engagement will grow into a long-term commitment.

We can thus compare one's relationship with the Torah's overarching message to an appreciation of the ark's golden facade. Instantly eye-catching and appreciable. But in passing encounters, the wooden ark structure escapes notice. What does its presence signify?

A famous verse in Mishlei describes the nature of the Torah as follows:

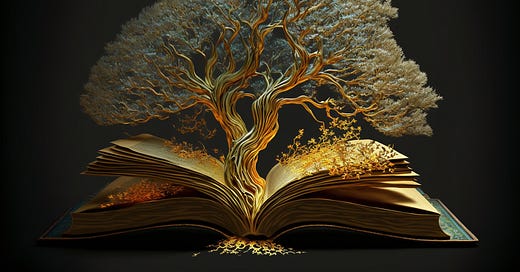

It is a tree of life for those who grasp it, and those who draw near it are fortunate.

{Mishlei 3:18}

The symbolism of this depiction is fundamental. Torah is not merely a rigid set of laws but a living, breathing national endeavour. Like a tree, its roots are firmly planted in tradition, but its body and branches are constantly developing. And yet this reality is only visceral 'for those who grasp it', for those intimately involved in the perpetually unfolding process. This reveals the more profound significance of a wooden ark enshrined in gold:

Whilst the holistic moral message of the Torah can be breathtakingly inspirational, its lifeblood and spirit is the living halachic process.

We should note, however, that an individual cannot easily experience this reality at a cursory glance. Much like the wood at the centre of the ark, one must become familiar with Torah to appreciate its eternal essence.

One of the blessings of modern innovation has been the proliferation of Torah works in English. We have distilled the entire edifice of Halacha into bite-size rule books and catchy three-minute clips. Thanks to this changing reality, the general religious Jewish populace has a far broader awareness of fundamental Jewish law. Yet something has also been lost by the approach we have taken to Torah. By encountering Torah in easy-to-understand English textbooks, we also miss out on tasting the sweetness of an intimate connection with its source. Rav Moshe Shapiro would often bemoan the subtle meanings lost through Torah’s translation into English.

Much has been written and said about the need to invigorate Judaism with a sense of warmth and relatability. On this, I entirely concur. Indeed I am personally attached to chassidus and machshava in general. Yet something must also be said for what some can regard as an 'old school' approach. Nothing is more fulfilling than immersing oneself in the infinite waters of challenging textual study. It is certainly not what may appear attractive about Judaism at first glance. It lacks the apparent beauty of the golden casing of the Ark. But to spend time absorbed in the world of Torah is to connect to a living legacy. To grasp hold of the tree of life itself.

Good Shabbos, and Keep Pondering

My own take is that the more the moral foundations of mainstream society crumble, the more apparent it is to the honest how beautiful the Torah way of life is. It requires less and less sophistication and immersion to discern.